September 6, 2013

So spoke Tariq Ramadan, professor of contemporary Islamic Studies at Oxford University, at the Islamic Society of North America’s 50th Annual Convention that took place August 30-September 2 in Washington, D.C.

In 2010 Christians noted 100 years of work for unity among the followers of Jesus in what has come to be known as the ecumenical movement. And Muslims are now laying the foundational principles for a corollary movement within their own ranks.

In a session titled “Saved Sect? Theology and Ethics of Pluralism.” Mr. Ramadan and Yasir Qadhi addressed the situation among Muslims where, as in Christianity, there are several branches – Sunni, Shia, Salafi, Sufi, just to name a few schools of thought within their community – with each school seeing itself as rightly guided and laying claim to being the “saved sect.”

As Christians did in the early part of the 20th century, Muslims are now asking themselves: How do we navigate the choppy waters of intrafaith diversity? How do we remain faithful to our particularities while accepting differences? Toward this end, Mr. Ramadan and Mr. Qadhi examined the theology of inclusiveness and the ethics of disagreement in building the beloved community.

Agreement on Essentials, Pacifism, Inclusivism

Mr. Qadhi, an Islamic lecturer and author of several books about Islam, emphasized agreement on the essentials of that faith, granting that “large segments of the umma (Muslim community) don’t care about these schisms, sects and marginal issues. The average Muslim doesn’t need to specialize in these questions. As long as he believes in the six pillars of Islam, prays five times a day, and accepts the Qur’an, it will be enough.”

Mr. Qadhi noted that no matter what theological position one holds, the Prophet Mohammad never sanctioned physical violence against someone who holds another position.

“If I am a Sunni, I cannot allow anyone to blow up a Shi’a shrine,” he said. “Argue what you want to argue, but allow others the freedom to believe what they want to believe. Scholars of all stripes need to understand that there is a time and a place and a methodology for talking about the divisive issues.”

“I might disagree with certain things in others’ interpretation of scripture,” Mr. Qadhi continued, “but it’s not my right to force my theology on other people. These schisms/sects will remain. Let Allah be the judge. We shouldn’t be threatening or harming one another. We should not be guilty of the sin of arrogance. I might believe that my theology is right, but that doesn’t mean I am a better person than the other. If we both believe we’re onto the truth, then we should follow the Qur’anic principle that truth should lead to humility. We should treat others as we ourselves wish to be treated,” said Mr. Qadhi.

Three Conditions

Mr. Ramadan picked up on the understanding of truth. “There is one humanity,” he said, “but Allah also wanted diversity within humanity. Diversity is both a challenge and a necessity. The only truth is with Allah.”

Mr. Ramadan cited three conditions required for all Muslims to live together peacefully: “One, we need to respect the sincerity of the other, to grant the good intention of the other. We must always start with this.

“Two, competence. Talk at the level of your knowledge. If you don’t know, refrain from judging. And if you do know, then exercise your competence with respect.

“Three, be careful. Respect the boundaries.” His reference here was to the Ahmadiyyas. a reform movement that grew out of Sunni Islam. It was founded in 1889 in India by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who claimed to be the metaphorical second coming of Jesus and the divine guide whose appearance was foretold by the Prophet Mohammad. Most Ahmadis believe he was the long-awaited mahdi or messiah.

But since in Islam the notion is that the Prophet Mohammad is the last of the prophets, the question then becomes in the eyes of many other Muslims: Are these people really Muslims or not?

Mr. Ramadan’s response. “In the case of the Ahmadiyyas who believe there is another prophet after Mohammad, it’s no longer an intrafaith dialogue, but an interfaith dialogue.”

The overall discussion was one that strikes familiar chords for Christians, who have had and continue to have their own struggles around scriptural interpretation, doctrinal distinctions between essentials and non-essentials, and questions around whether certain reform movements (like the Mormons) are to be recognized as Christians or not.

In the end, any gains made relative to unity among Christians and unity among Muslims will have positive and far-reaching repercussions within the unity of the human family at large. We will do well to empathically support each other’s efforts and celebrate each other’s progress. In the big picture, there is just one human family, and everyone in it is a child of God.

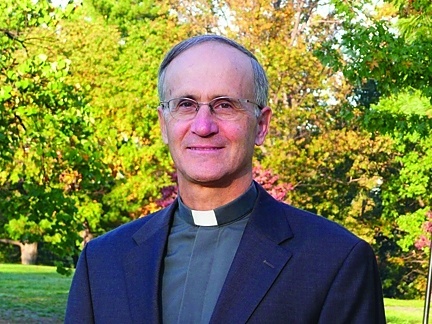

Father Thomas Ryan, CSP, directs the Paulist North American Office for Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations in Washington, D.C.