April 11, 2018

Mr. Velsor lived in our building on West 62nd and Amsterdam Avenue, but I especially liked the times I ran into him as he drove his New York City bus up and down 59th Street. A child gets fascinated when trying to connect a private figure with a public one — “Is this the same man who lives upstairs?”

But Mr. Velsor also stays in my mind because, whenever priests and nuns got on the bus, he would discreetly put his hand over the machine that took our coins or tokens. He would wink and let the religious people move back into the bus without paying. (This was in the early 1950s.)

This speck of memory I have of riding the bus across 59th Street opens up so many other memories, of a time when daily culture, city life, and faith seemed seamlessly woven. Of course, this was before they began building the New York Colosseum, when 59th Street still was a major road east and west. While I vaguely remember some of the stores and shops around Columbus Circle — Regal Shoes, with the large bronze image of a boot suspended in air over the doorway — I mostly remember the experience of moving from the jammed and darkish 59th Street corridor between Tenth and Eighth avenues to the relative brightness of a busy Columbus Circle itself. The air and light of Central Park made Columbus Circle shimmer.

Older Paulist priests would talk to me, later in life, about Columbus Circle — how in the early decades of the 20th Century it represented a place of certain forbidden pleasures offered among other conveniences for the thousands who commuted through there — the older Paulists would sometimes be embarrassed walking down the street! And especially how closing off 59th Street, after the Colosseum was built, blocked the East Side of the city from direct access to the Paulist Mother Church, St. Paul the Apostle. When one of the older Paulists expressed this smoldering resentment at the blocking of 59th Street decades later, it underscored my primary impression of growing up in St. Paul the Apostle Parish: the parish was important — everything about it was important.

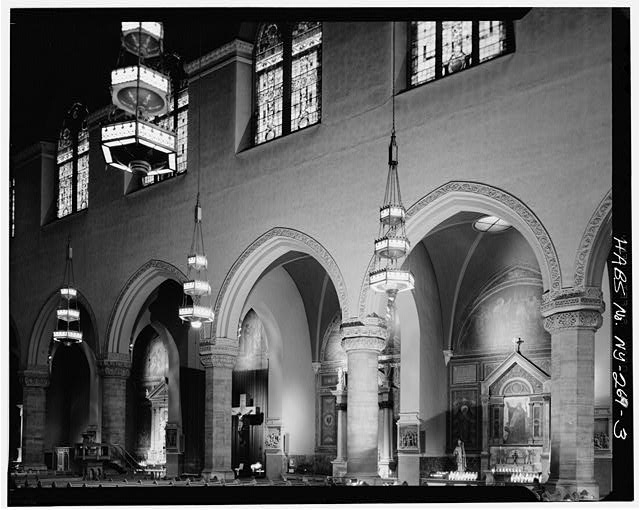

Generations before me would tell me of the phrase “growing up Paulist,” and “going to the Paulist church” as ways people differentiated themselves from other Catholic and city experiences. The “Paulist Church” stood out — not merely its vastness (a cousin said to me once, “Seven of my parish churches could easily fit into St. Paul’s”), but the beauty of its interior decoration, notably the Stanford White main altar. Not least of all, the Paulist Fathers themselves made the “Paulist Parish” distinctive — they had publishing buildings near the church, had run a radio station from there, and they had Paulist-habited missionaries scouring the Northeast and the city, giving missions, retreats, and novenas.

To “grow up Paulist” was to have one’s personal status enhanced by this dynamic group of men who were bringing Catholicism to America and using every means of media to do that. Paulists would tell us fifth- and sixth-graders to tune in for this or that show on the radio, or maybe even see the Paulist Choristers appear on TV. We’d feel a special pride when someone whose mass we served — Fr. Reynolds, or Fr. Finley, or Fr. Lloyd — would also appear on television later. How amazing was it to see the church packed during missions and novenas as Paulists made that huge church echo with their booming — or sometimes whispering — voices.

Although we didn’t use the phrase “growing up Paulist” to describe our generation in the 1950s, we knew we were stamped, not only by the Paulist Fathers, but by the Holy Cross Sisters who staffed St. Paul the Apostle School with (during my years) over 1,400 Catholic school students. “SPAS” were letters on the logo we wore — blue and gold! — and Paulist priests would say to us, with a twinkle, “If you spell that backwards, it says SAPS!” The Sisters came with their reputations before them — “Don’t try this in so-and-so’s classroom’; or, “Did you see Sister pick that kid up from the floor?” Looking back, I cannot figure out how they did it: crammed into very small convent spaces, rising at 5 in the morning, teaching rooms jammed with over 50 children, and turning out students who could rank with any other student from any other school — those Sisters, often on their first assignments as teenagers, gave their lives to better generations of tenement-dwelling and their project-living schoolmates. Welcome to New York, Sister! Welcome to the West Side! No, I guess it’s not Indiana, is it?

Of course we know now that the 50s and 60s were both the apex of that marvelous social reality called the “Catholic parish,” but also the years just before the decline of both city and city parish. I graduated in 1959 with nearly 100 children divided into two eighth-grade classes. Less than 15 years later, St. Paul the Apostle School closed for good, with under 400 students in all the grades combined, many unable to sustain what was even then a modest tuition base.

My years at St. Paul’s seem framed by crashes. I remember some school of nursing on Tenth Avenue, between 59th and 60th streets, being demolished “the old fashioned way” by swinging steel balls into the sides of the thick stones that made up its walls. Even we children knew this was dangerous, but what did danger matter, back then, when there was building to be done? In its place came the Miles Shoe Company — a glorified warehouse for storing and distributing Miles Shoes. (This later morphed into the John Jay College of Criminal Justice which absorbed Miles Shoes and the former Haaren High School kitty-corner to it on 59th Street.) The closing of 59th Street allowed the construction of the New York Colosseum — which would bring annual shows from around the nation to our neighborhood: the car show! The boat show! “How can I sneak in?”

But in our minds, more memorable than the Colosseum itself was the massive collapse of the building three-quarters through its construction, when uncured cement from the top floor cascaded down to the floors below. We heard the boom about 2:30 p.m. in our classroom; the school and entire block shook. We left the school building at 3:00 to the screeching of sirens and horns as emergency vehicles tried to save the worker’s lives.

I still remember newspaper photos of Paulists crawling through debris, attempting to anoint the dying and the dead. Paulists told me that every priest left the rectory, each prepared for the gruesome ministry of caring for dying construction workers and consoling their families. To be a priest was to regularly deal with death. One of my mentors, Fr. Frank Diskin, made it, sadly, to the front page of The Daily News, anointing what remained of some poor worker.

Mingled with these memories of crashes was the 1957 renovation of St. Paul the Apostle Church. Fr. John Carvlin — an inevitably joyous man — was the pastor. Even before the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, I remember it being explained to me that the decorations of the church building were going to be simplified, paintings of prophets (spelled with the Duay-Rhiems tradition of tending toward the Greek—Isaias, not Isaiah) and other images were removed; a uniform coat of gray paint dulled the walls: all of this was to help people focus on the main altar, the Mass, and not be “distracted” by less important things. At some point the church was filled, wall to wall, with scaffolding. “There’s thunder out west,” I heard one Paulist say to another who was going out to try to celebrate Mass at one of the numerous side altars that priests used at that time. Workers were dismantling the old church ceiling, thousands of square feet of plaster, creating endless booms of noise and dust, until it seemed that, whatever the initial plan, we would have to move everything down into the auditorium below the Church, until renovations were done in time for the 100th Anniversary of the Paulists in 1958.

During this time the church building received two works of art that would define its exterior and interior. Lumen Martin Winter, the chosen architect (who would later adorn Grand Rapids with memorials of Gerald Ford), had created for the outside front of the church the “largest bas relief in the world” — a symbolic scene of the conversion of St. Paul against an ocean of blue mosaic. This was accompanied by the sarcophagus for Fr. Isaac Hecker — the massive white-marble structure by the entrance near 60th Street which would hold whatever was left of Hecker’s body as it was solemnly transferred from the lower crypt burial niches near 59th Street on a cold January in 1959. I remember rows of Knights of Columbus, arrayed with swords and plumed hats, adding to the no-holds-barred liturgy of that transfer. I also remember how the 60th Street entrance was closed for months as steps were dismantled, and steel inserted, to permit the sarcophagus’s entrance into the church. Marble on the outside, marble on the inside — St. Paul’s was ready for the future.

But St. Paul’s could never be ready for the immediate future that was already underway and indelibly shaping the Paulist parish. Beginning in 1958, blocks of our parish was designated for “urban renewal” — which meant that urban designer, Robert Moses, was going to tear down the houses and apartments of my classmates in order to make way for Leonard Bernstein, Fordham University, and scads of people who were not natural to the West Side. Hello Lincoln Center! I occasionally see pictures on Facebook of block-long scaffolding in front of now-emptied tenements as more steel-balls were readied to demolish more of our neighborhood. We lost over ten thousand parishioners in two years. An era was ending before our eyes.

I think they started on 63rd street, the street with the most “Spanish speaking,” and proceeded to demolish, month by month, blocks of tenements, a huge Armory, and anything that stood in the way of progress. Classmates vanished overnight. I remember walking down Amsterdam Avenue one afternoon, toward the public library on 67th street, and looking west where dancers were being filmed for the opening scenes of “West Side Story.” After the filming, those buildings vanished too, along with St. Matthew’s parish on 67th and 11th whose existence is now attested to from the gym scenes in that movie. “When you’re a Jet, you’re a Jet all the way. . . .”

While Paulists sometimes took pride that our mother church would be situated next to the greatest cultural center in the world, many Fathers realized that the parish would no longer be the same: that collection of pre- and post-war ethnic families whose lives centered on the parish church. Indeed, St. Paul’s, probably more than most parishes, served as a cultural center for thousands of people. Children were parsed into various groups that bound us more intensely to each other and the Catholic urban experience — Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, C.Y.O., the choir, and the altar servers. These groups, and off-the-cuff after-school programming, cemented people to each other. I look back at my eighth grade graduation certificate and stare at the scores of photos of my peers: I actually had no idea then how “diverse’ we were — mixing whatever race we children might belong to because, underneath, we were all survivors of New York — it’s hardships but also its beautifully intense experience of humanity.

Parents belonged to the “Mothers Club” or the “Fathers Club.” One evening I remember what would today be very politically incorrect: a “Father and Sons” smoker sponsored by the Father Club, when the daddies received big cigars to smoke and we sons dreamed of the day when we would be free to smoke as well, all while watching a film, either Cowboys-and-Indians or something about gangsters. Not long after this, perhaps two years, I remember New York City detectives abruptly visiting our classrooms. “Don’t touch anything and stand along the sides of the walls.” Police were going through our pockets and our desks: the era of drugs had arrived, something that would drive the greatest wedge between some fathers and their sons for decades to come.

St. Paul the Apostle parish today still has not recovered from this massive pillaging of its housing stock. Subsequent years had church attendance fall below 700 for all Masses on Sunday — when I was a child attendance was well above 10,000 every Sunday — and religious education attendance dwindled to just scores of children. Maintaining St. Paul’s meant heroic struggling, particularly after the plan for its demolition-and-replacement fell apart in the mid-1970s. Paulists today would look at this failure with a wry smile because of the huge pride we take in the church that Father Hecker dreamed of; nevertheless, even with the selling of property and buildable air rights, the parish could never return to the pre-Lincoln Center stability of thousands of ethnic Catholics for whom parish was a means of survival.

To keep St. Paul the Apostle church would mean a constant uphill battle with finances and maintenance, and an even more strenuous struggle to situate the parish in a broader pattern of urban life. With the development of the land above the railroad tracks down beyond 12th Ave. (land with which Mr. Donald Trump’s name was associated), perhaps in some ways the housing stock has started to rebound — but with a very different, and often out-of-town population. While it is clear that the 1950s can never return to St. Paul the Apostle — a lesson burned into our ministerial lives over these decades — this lesson seems unlearned for the wider Church which still thinks — presto! — the crowds and identity of the 1950s might just somehow return.

Wherever I go, I keep running into people whose lives were shaped by St. Paul the Apostle parish. “My parents were married there.” Or, “I was in the 1957 class, what was your class?” While these memories are doomed to recede as time pushes forward, St. Paul the Apostle stands as a marker of the role church played for generations of people flocking to the city for something better. The housing projects, Amsterdam, remain as viable housing some 70 years after their construction — they were probably the first urban upgrade in the parish. My family moved into Amsterdam in 1948, just as they finished the buildings that line Amsterdam Avenue; I can walk into that building today and sweep back seven decades of my life. The aromas and noises are different, as is the crime people fear today (though today much less than in the 1980s when I served as pastor and saw lives regularly ruined by drugs and HIV), but, like St. Paul’s itself, a defiant edifice to a city that insists on changing.

Many of my peers remember being taken, en mass, from St. Paul the Apostle School, across blocks of rubble from demolished tenements; we were in the seventh or eighth grade. Along with others from the city, we were treated to folding chairs as, on a clear fall or spring day (I can’t remember which), we saw Leonard Bernstein conduct the Philharmonic Orchestra outdoors — the down payment of the cultural dreams that allowed Lincoln Center and Fordham to thrive, but the harbinger of sparser years for the parish. Of course, few people wielded a baton as did Leonard Bernstein; I’m sure Copeland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man” was among the offerings.

But St. Paul the Apostle was, throughout its history, a living fanfare for common people — gathering into itself decades of people whose hopes and sufferings were celebrated by liturgies both solemn and quiet. Paulists did not at all discriminate when it came to opening their hearts and doors. I well remember the array of Paulists who received the envied assignment (!) of “organizing” the altar servers. Fathers Burt, MacDonald, McQuade, Pietrucha, Sheehan — each tried to impress upon us city kids the importance of punctuality and cleanliness. We older servers helped the younger ones don their capes and tie those red or white bows before High Mass — “Where do I stand?” “Just follow me and don’t screw up!” We vied to be “altar boy of the month” — and to carry the cross, or swing the thurible, or secretly make faces at the choir boys who were trying to sing behind us. We vied for a moment’s fanfare.

In the end, my memories of St. Paul the Apostle parish underscore for me a life-long lesson: underneath, we are all common women and men. Behind the ordinariness of our lives — whether blue collar or white — two rhythms play. One, the rhythm of a rather monotonous daily life, centered on hard work and punctuated by moments of fun. The other rhythm, harder to hear, is comprised of those trumpets announcing the boldness and dignity of every urban dweller — especially those on the old West Side, just above Hell’s Kitchen, and just before the glaze of luxury that Lincoln Center brought.

St. Paul’s played both rhythms so well, gathering into self an astonishing hodge-podge of humanity, most of us poor but not knowing it; and surrounding us with a vision of humankind and God that buoyed us in the worst moments of our lives — that swept us beyond our tenements and smelly-elevators to the belief that we could touch God because God had touched us through our parish. St. Paul’s made our lives important when we had the least reason to believe they were. It filled our heads with broader dreams than most urban life could, in those mid-century years, provide us. Amid the booms — and busts — of New York urban life, St. Paul’s stood there, a testimony to God’s presence shaped in stone and marble, a community of forward-thinking priests and people who were not going to let life get the better of them.

As I cherish so many moments of my childhood — every generation of New York City kid has affirmed this cherishing — I wonder, if a time machine could transport me back, what I really would see. Would I, from my relative comfort, cringe at the shape of the tenements that were demolished, or shake in fear to climb the stairwells in the Amsterdam Projects? Do I need to romanticize a life that had little basis for embellishment? I wonder. But I do know that St. Paul the Apostle suffused our lives with so much color and greatness; even as it embraced so much of our everyday heartache. That’s what defined its history — and, to be sure, always will.

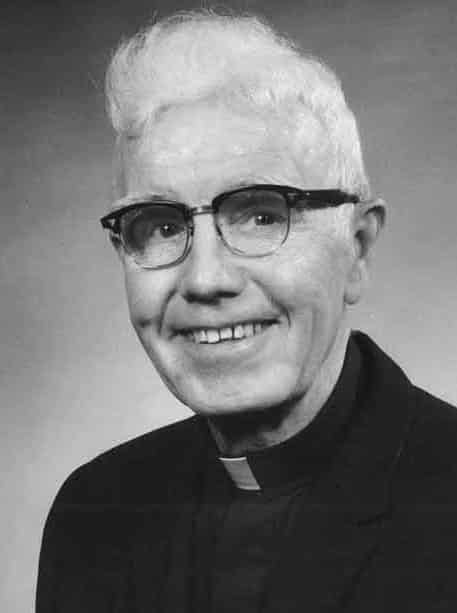

Paulist Fr. Frank DeSiano is president of Paulist Evangelization Ministries and director of formation at our seminary in Washington, D.C. He served as president of the Paulist Fathers from 1994 to 2002.

Ordained a priest in 1972, Fr. Frank was pastor of the Church of St. Paul the Apostle in New York City from 1978 to 1984.

Listen to an interview with Fr. Frank about his life and ministry.