July 16, 2012

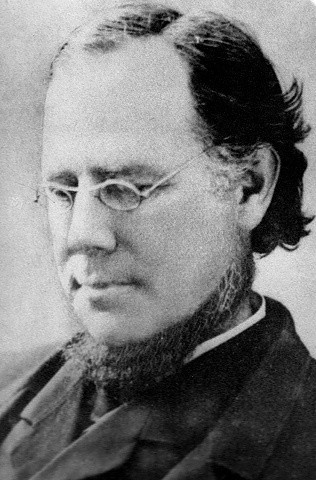

This is the thirteenth in a series of previously unpublished reflections from the 1854 spiritual notebook of Paulist Founder, Servant of God Father Isaac T. Hecker. The reflection series is being made pubic in conjunction with Father Hecker’s cause for canonization. This week’s reflection is the sequel to last week’s offering and includes a response from Father Tom Ryan, CSP.

Let us not forget that our great and only work is not, as some imagine, to copy some ideal model which however beautiful it may be in itself, is of no value at all to us; but it (our only work) is to restore and sanctify our fallen and corrupt nature.

“Without me you can do nothing.” (John 15:5) God has created us for a destiny which we cannot attain with our natural powers unaided by grace. The highest and the perfect development of our whole nature depends on being in true relationship with the end of our being: God.

“The vanity of asking for knowledge without God. The vanity of seeking to satisfy the heart without God. It is not me you seek says the rose, the stars. The vanity for living for any other than God: honors, riches, pleasures.” Blessed Henry Suso, German Dominican mystic (1300-1366).

What is the end of man? The intellect answers, to know God, to contemplate and admire His infinite beauty, wisdom. The heart answers, to love God, to love God in all things and particularly in His own image, man. To love God above all things because He alone can satisfy and fill our hearts. What is the end of man? The will replies, to live, labor and suffer for God and for God alone, for He only is worthy of our life and a worthy end of our actions. To know, to love, to serve God, this is the true end of man.

The light eternal which to see alone

Ne’er fails to kindle love; and if aught else

Your love seduces, tis but that it shows

Some ill marked vestige of that primal beam.

The Divine Comedy, Paradise, Canto 5, Dante Aligheri (1265-1321)

“God has created us for a destiny which we cannot attain with our natural powers unaided by grace.”

As one who came from a Protestant background and wanted to focus his message to the Protestants who were in the crowd at his mission preaching, Isaac Hecker was attentive to dominant themes in Reformation spirituality such as “our fallen and corrupt nature.” At the same time, he had a very positive assessment of the marvelous things this nature is capable of when it is permeated with and guided by the transforming grace of God, a.k.a the Holy Spirit.

When he quotes the German mystic Suso to the effect that living for anything other than God – honors, riches, pleasures – is short-sighted, his response is like that of Jesus when he was asked by the Pharisees and Herodians if it was lawful to pay the tax to Caesar or not. “Repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God.” And what belongs to God? Our hearts and our lives.

His experience in communal living at Brook Farm and Fruitlands showed Isaac the Seeker that a person’s life cannot be made secure by what one owns, but by who one is. Not surprising, then, that after his conversion to Catholicism and founding of the Paulists, a driving theme in Hecker’s vision of Paulist ministry is conversion – the movement toward God in recognition of how truly poor our own nature/self/ego’s are. There is almost a complete correlation between the amount of fear in our lives and the amount of attachment we have to ourselves and our possessions. But in God lies the path from fear into freedom. “To know, love, and serve God, this is our true end.

His quote from Dante’s Comedy about eternal light evokes some verses of my own:

Few things I hold more dear

than the quality of light

whose many moods by day

become more precious in the night.

There’s a truth revealed here

to be never lost from sight,

that at the end of all our days

we’re meant to pass from light to Light.

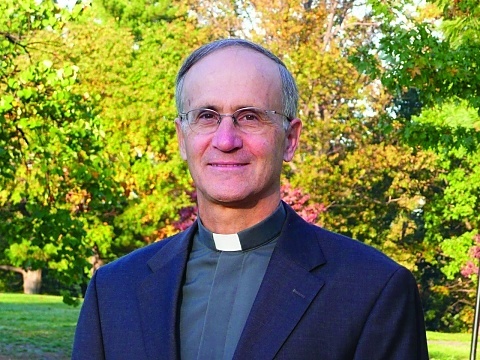

Father Thomas Ryan, CSP, directs the Paulist North American Office for Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations in Washington, D.C.

About Father Isaac Hecker’s 1854 Spiritual Notebook:

Servant of God, Father Isaac Hecker wrote these spiritual notes as a young Redemptorist priest about 1854 and they have never been published. Hecker was 34 years old at the time, and had been ordained a priest for five years. He loved his work as a Catholic evangelist. The Redemptorist mission band had expanded out of the New York state area to the south and west, and the band’s national reputation grew. Hecker had begun to focus his attention on Protestants who came out to hear them. To this purpose Hecker began to write in 1854 his invitation to Protestant America to consider the Catholic Church, “Questions of the Soul” which would make him a national figure in the American church.

Hecker collected and organized these notes that include writings and stories from St. Alphonsus Liguori, the Jesuit spiritual writer Louis Lallemant and his disciple Jean Surin, the German mystic John Tauler, St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Jane de Chantal among others. These notes were a resource for retreat work and spiritual direction and show Hecker’s growing proficiency in traditional Catholic spirituality some ten years after his conversion to the Catholic faith. They are composed of short thematic reflections.