July 2, 2012

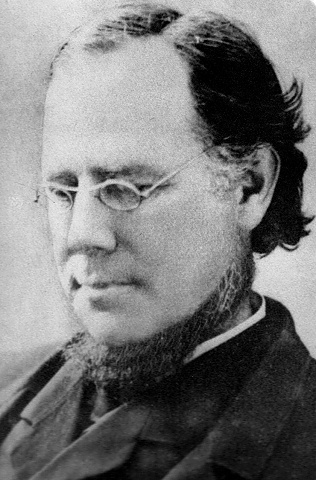

In light of the Fourth of July holiday and the U.S. Bishops’ Fortnight for Freedom, this eleventh in a series of reflections from Paulist Founder Father Isaac T. Hecker diverges from the original format. This week, Paulist Historian Father Paul Robichaud discusses Father Hecker’s belief that Catholicism and Democracy are compatible and complimentary and how that belief is a commentary of the issues facing faith and freedom in America today.

Freedom

The recent statement of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops on “Religious Liberty” and their call for “A Fortnight for Freedom” (June 21 to July 4) – a period of public action to highlight the importance of defending our first amendment freedom to religious practice – raises the question of what Paulist founder and Servant of God, Father Isaac Hecker (1819-1888) might say about American freedom. The opening paragraph of the Bishop’s letter could have been written by Father Hecker himself, who believed in the compatibility of the Catholic faith with American democracy. The bishops write: “To be Catholic and American should mean not to have to choose one over the other. Our allegiances are distinct but they need not be contradictory, and should instead be complimentary. That is the teaching of our Catholic faith … that is the vision of our founding and our Constitution.”[1]

Father Hecker held that Roman Catholicism, with its emphasis on the rights and freedom of humankind made possible through the universal invitation to reject original sin and become a child of God through the death and rising of Jesus, provided a theological basis to affirm human dignity and human rights. Father Hecker often compared the positive and inclusive teaching on human dignity in Roman Catholicism to the churches of the Reformation, which Father Hecker believed emphasized the depravity of humankind and its loss of freedom. Catholicism was for Father Hecker a better fit with American democracy; a governmental system built upon natural rights and freedom.

Father Hecker wrote an extensive reflection on the Declaration of Independence, whose origins he found in the Magna Carta of 1215. For Hecker the Magna Carta was a Catholic document made possible through the intervention of the Catholic bishops of England with King John at Runnymede. Hecker wrote on the Catholic origins of the Declaration:

“That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among them are life liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Father Hecker wrote: “That some of these [declarations] are divine and fundamental truths and all are practical verities having a ground in both reason and revelation. They are divine inasmuch as they declare the rights of the Creator in His creature; they are fundamental, for without the enjoyment of the natural rights which they proclaim, man is not a man but a slave or a chattel; they are practical for man is, or ought to be, under his Creator, the master of his own destiny and free from any dominion not founded in divine right. The Creator invested man with these rights in order that he might fulfill the duties inseparably attached to them. For these rights put man in the possession of himself and leave him free to reach the end for which his Creator called him into existence. … And if there is any superior merit in the republican policy of the United States, it consists chiefly in this: that while it adds nothing and can add nothing to man’s natural rights; it expresses them more clearly, guards them more securely, and protects them more effectually; so that man under its popular institutions, enjoys greater liberty in working out his true destiny.[2]”

Both the Bishop’s letter and Father Hecker make reference to the address of Cardinal Gibbon’s (1834-1921) on the occasion of his taking possession of his titular church in Rome in 1887. Father Hecker cites the second American cardinal: “For myself as a citizen of the United States, and without closing my eyes to our shortcomings as a nation, I say with a deep sense of pride and gratitude that I belong to a country where the civil government holds over us the aegis of its protection without interfering with us in the legitimate exercise of our sublime mission as ministers of the Gospel of Christ. Our country has liberty without license and authority without despotism.”[3]

The First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion. Father Hecker believed that this meant that the government should give established churches broad latitude to operate within their religious teaching. Responding to Gibbon’s address Father Hecker wrote: “Here in America when the church and state come together, the state says, I am not competent in ecclesiastical affairs, I leave religion in its full liberty. That is what is meant by the separation of church and state. … By ecclesiastical affairs we mean the organic embodiment of Christianity, which the church is in her creeds, her hierarchy and her polity. The American state says in reference to all of this, I have no manner of right to meddle with you; I have no jurisdiction.[4]”

Again Hecker wrote in his monthly, The Catholic World: “For the principle of the incompetency of the state to enact laws controlling matters purely religious is the keystone of the arch of American liberties.[5]”

Between 1881 and 1883, Father Hecker responded to criticism coming from the secular press over the Catholic Church’s massive investment in its own parochial school system. Many non-Catholic Americans considered the public school system not only an American achievement but also an essential and formative base for producing good citizens. The Catholic decision to build a separate educational system convinced many critics of the Church that Catholics were not good Americans. And the suggestion that public taxes paid by Catholics could be used to support a separate parochial school system deepened the hostility. Father Hecker favored the idea that tax dollars could support parochial schools, reducing what he called the double burden of Catholics paying twice, first in taxes and secondarily in financial support for Catholic schools. In parallel fashion to the present situation between Catholic institutions and the federal government where the government seeks some compromise from the church, Father Hecker argued in the 1880s that compromise on the part of the church is not possible if the church is to be faithful to her beliefs. Father Hecker wrote: “The educational question, properly understood, is a religious question. It is a question of enlightened religious convictions – convictions most sacred of the rational soul … To expect that these can be accommodated, or adjusted, or compromised on a common basis is to ignore what is at stake … Let us understand this and each work in his own sphere, respecting each other’s religious convictions.[6]”

The Fourth of July is an occasion to remember our American Revolution and the nation building that followed. For Catholics living in the new nation, anti-Catholic restrictions in state constitutions were struck down after the Revolution and the First Amendment guaranteed the free exercise of religion. Today’s American government is based on the foundation of universal suffrage, something that only began in the Revolution and continued for more than a century until the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments were enacted. On this Fourth of July, Father Hecker’s words in the 1887 Catholic World have a rhetorical flair:

“Universal suffrage is the most efficient school to awaken general intelligence, to teach a people their rights and to arouse in their bosoms a sense of their human dignity. For what is a vote? It is the recognition of our intelligence and liberty and responsibility; the qualities that constitute our human dignity. What is a vote? It is the admission that our human rights are a factor in political society, and that we have the right to shape and the bounden duty to shape so far as our ability extends, the course of the destiny of our country. A vote is a practical means by which every voter can exercise their rights and fulfill their duty by making their voice heard in the councils of the nation, it is the practical application of the truth, ‘that all men’ have an equal right ‘to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,’ and armed with a ballot we have the power of maintaining and protecting these rights. [7]”

Footnotes:

[1] “Our First Most Cherished Liberty: A Statement on Religious Liberty,” USCCB Ad Hoc Committee for Religious Liberty, March 2012, p. 1.

[2] “The Catholic Church in the United States,” The Catholic World , July 1879, pp. 438-239, and later reprinted in The Church and the Age (1887).

[3] Cardinal Gibbons on his taking possession of his titular church in Rome, March 23, 1887, The Church and the Age, pp. 113-114.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “The Catholic Church in the United States,” p. 434.

[6] What Does the Public School Question Mean?, The Catholic World, October 1881. pp. 88-89.

[7] “The Catholic Church in the United States,” p. 442.