February 15, 2017

Paulist Fr. Rich Andre preached this homily for the 6th Sunday of Ordinary Time (Year A) on February 12, 2017 at St. Austin Parish in Austin, Texas. The homily is based on the day’s readings: Sirach 15:15-20; Psalm 119; 1 Corinthians 2:6-10; and Matthew 5:17-37.

We have a relatively long gospel passage today that covers a lot of different ideas: how Jesus claimed to “fulfill” the Law and the prophets, how Jesus raised the bar on upholding the commandments, what he says about anger, name-calling, and lust. And if that isn’t enough, Jesus also speaks about divorce and remarriage. Obviously, we can’t dig into all these ideas in detail in one Mass.

The community to whom Matthew was writing was a group of people didn’t feel as if they fit in with anyone else. They were Jewish Christians, who felt rejected by both Jews who weren’t Christians and Christians who weren’t Jews. At various points in our lives, we have all probably had the experience of feeling as if we don’t belong, too. We are destined for the perfection of heaven, but we are imperfect people living on earth. Let us take a moment to acknowledge that we rely on God’s mercy to cross the divide.

By the time that Matthew wrote his gospel, political events had made Jewish Christians feel isolated from both the majority of Christians who were Gentiles and from the majority of Jews who rejected Christianity.

If we take certain verses out of context, Matthew appears to be condemning the Law (5:34), the Pharisees (5:20), the entire Jewish people (27:25), and the Jewish religion (21:43). However, if we consider Matthew as a whole, it gives the most positive portrayal of Judaism in the four gospels. Matthew presents Jesus as the new Moses, giving the Sermon on the Mount in a way similar to Moses receiving the Ten Commandments on Mt. Sinai. Jesus himself declares, “I have not come to abolish [the Law or the Prophets], but to fulfill” (5:17).

Nevertheless, through the centuries, the Gospel of Matthew has been used by many Christians to persecute Jews. For centuries, the Church promulgated a theology that has been called “supersessionism,” “replacement theology,” or “fulfillment theology” – claiming that by rejecting Christ, Jewish people had rejected their status as God’s chosen people. After such theology had been used to justify the Holocaust, the Second Vatican Council condemned all acts of aggression against Jews, saying “[T]he Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures…. [T]he Church… decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.” (Nostra Aetate, 4) Every pope since then has advanced this embrace of Judaism. For example, St. John Paul II described Jews as our “elder brothers [and sisters] in the faith of Abraham.” Christians today have a responsibility not only to fight all forms of anti-Semitism, but also to undo nineteen centuries of damage from previous disputes.

Jesus says that he has come not to abolish the Law but to fulfill it. But then he teaches ways in which he says the commandments of the Torah do not go far enough. But some of the standards he sets up seem impossible to achieve. Calling your brother a blockhead (or ‘raqa’) is a sin, but anger is a God-given emotion that even Jesus experienced. We should live chastely, but we will probably continue having sexual thoughts until our brains cease to function. It probably made sense to tighten up the Jewish law about divorce since it was very relaxed for the husbands and very difficult for the wives, but Jesus’ complete prohibition of divorce is more stringent than what the Church advocates today.

Some of what Jesus says in this part of the Sermon on the Mount is clearly not meant to be taken literally. (For example, in next week’s passage, I doubt Jesus is calling for public nudity in 5:40.) This can be quite disconcerting, however, when we pair this gospel passage with Sirach’s entreaty to keep God’s commands and a psalm that praises those who observe the Law’s decrees, and when we note that Jesus has just finished condemning those who do not obey the smallest jot or tittle of the Law.

Jesus recognizes the challenges of being human. The Torah’s rules regarding murder and adultery are the bare minimum we should achieve, but we should aim for the perfection of heaven, even if we will fall short. Indeed, many rabbis in this period were advocating similar interpretations of the Law as Jesus.

There are so many ways that we, as humans, live in constant transition between one state of being and another. Our identities are not static. One facilitator working with the Paulists said to us, “we are constantly becoming.” We move towards a future guided by our past. The people of Matthew’s community struggled with their identities as both Jews and Christians. The kingdom of God is already here, but our eyes have not seen and our ears have not heard what God has prepared for us.

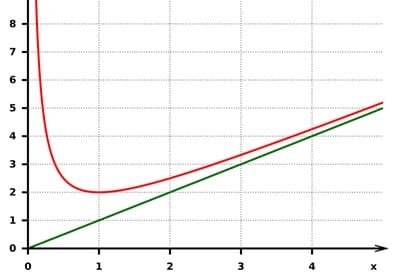

Or, to put it another way: the life of holiness is like a curve on a graph that approaches a line asymptotically – that is, it gets closer and closer to the line, but it won’t touch it until infinity. So it goes in the life of holiness. Hopefully, we get closer and closer to Christian perfection throughout our lifetime, but we won’t reach perfection until we get to heaven.