May 20, 2013

The land was once a cornfield on an unpaved Fourth Street in rural northeast Washington, D.C. A trolley car ran down the middle of nearby Michigan Avenue, and there was a view the Washington Monument and Capitol Building.

The scenery might have changed in the 100 years since the cornerstone of St. Paul’s College was laid, but the Paulist spirit imprinted on each person who walked through these doors remains strong.

To mark the centenary anniversary of St. Paul’s College, a weekend of celebrations has been scheduled for May 17-19 on the historic campus. Event information will be posted on paulist.org when available, but will include an anniversary Mass and dinner and a keynote address by J. Bryan Hehir, SJ, professor of the practice of religion and public life at the Harvard University Kennedy School of Government.

“St. Paul’s College is where legacy of all of the Paulists seminarians of the past are instilled in the Paulist students of today as they prepare for their future ministry,” said Father Paul Robichaud, CSP, Paulist historian.

After the Paulist Fathers were formed in 1858, Paulist seminarians lived and were educated at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle. St. Paul was the first Paulist parish and home base of the first Paulist mission bands. In the aftermaths of the Civil War, some 60 men and boys entered Paulist formation.

“About 30 of them became Paulist priests,” said Father Paul Robichaud, CSP, the Paulist historian. “It is a fascinating story because you trained where you were going to work.”

The seminarians lived on the first floor of the building, while some 10,000 of the faithful attend Sunday Mass on the first-floor church, according to Father Robichaud.

“They lived, studied and trained surrounded by parishioners,” he said, noting the seminarians helped with the choir and religious education.

Paulist Founder Servant of God Father Isaac T. Hecker was a fierce advocate for the founding of a national Catholic university, according to Father Robichaud.

“At the time, no one knew what Georgetown University or Notre Dame University or Boston College would become,” Father Robichaud said. “He very much believed in establishing a national university that would be the center of Catholic academic and intellectual life.”

Although he did not live to see the founding of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., in 1889, the community he started was the first to open a house of studies on the campus. That house was named St. Thomas College, in deference to St. Thomas Aquinas.

“Although listed as part of the new university, most of the Paulists were not formally enrolled there, as Catholic University was considered a graduate school,” said Father Robichaud. “The Paulist students were taught theology, scripture, philosophy, canon law, church history, Latin and rubrics by an in-house Paulist faculty, supplemented by university resources.”

Paulist students led a strict and stark existence, but did enjoy being witnesses to history.

“They witnessed a large parade of suffragettes who were seeking a constitutional amendment that would give women the right to vote in March 1913,” Father Robichaud said. “The very next day they saw the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson, which the student keeping the house diary wrote, was ‘the most inspiring spectacle ever staged in Washington.’”

Cardinal James Gibbons blesses the cornerstone of St. Paul’s College, 1913.

After more than 20 years of service, Paulist program of priestly education and formation had outgrown the expanded facilities of St. Thomas College. The Paulists decided to move their house of studies to farmland just south of the previous location. Cardinal James Gibbons, archbishop of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, blessed the cornerstone on Nov. 29, 1913. Archbishop John Farley of New York preached the day’s sermon. Although the building was occupied, it wasn’t until the completion of the chapel in 1916 that Paulist Superior General Father John Hughes officially named the facility St. Paul’s College.

One early rector of St. Paul’s, Father James Devery, sought to make the college financially self-supporting. The Iowa native installed a large chicken coop on the grounds complete with guinea hens. A tractor and farm equipment soon followed.

“At one point there were about 1,500 chickens on the grounds,” said Father Robichaud. “The director of the Old Soldier’s Home was so impressed, he started a chicken coop there that provided competition for the Paulists.”

Due to the time and effort the seminarians had to dedicate to the chickens and grounds, the farm experiment was short-lived. Future Paulist leaders would instruct new rectors of Saint Paul’s that while students may be assigned house chores, manual labor was not to interfere with studies.

“Cardinal Patrick Hayes of New York, a frequent visitor to St. Paul’s, was delighted with the news, as the guinea hens had often kept him awake,” recalled Father Robichaud.

The St. Paul’s College building takes shape

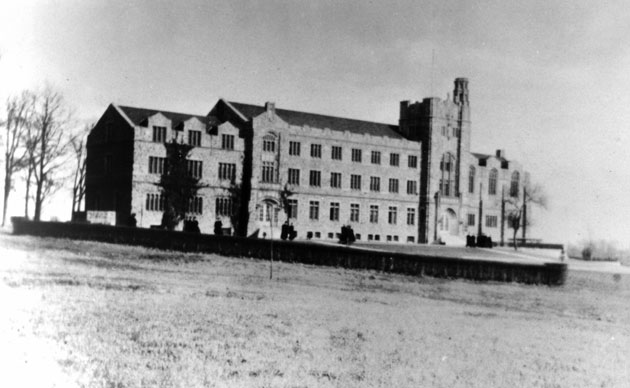

The completed St. Paul’s College building has few neighbors in then-rural Northeast Washington, DC

By the 1920s, the student body of St. Paul’s necessitated that the Paulist deacons move to the Apostolic Mission House, built on the university campus in 1904.

“This was a school and residence for diocesan priests who studied missiology under Paulist instruction in order to create diocesan sponsored mission bands,” Father Robichaud explained.

After the Apostolic Mission House was condemned in 1941, a new wing was constructed at St. Paul’s to accommodate both the work of the Mission House and the needs of the Paulists.

Increased enrollment meant more physical expansion of St. Paul’s in the 1950s. Non-Paulist students began attending St. Paul’s in the 1960s, including seminarians from dioceses in Cuba, India and Brazil. The Marists began sending their seminarians to St. Paul’s in 1967.

The Second Vatican Council and civil unrest of the 1960s made for exciting and dramatic times at St. Paul’s. Enrollment decreased, several of the younger faculty members had not only left St. Paul’s but also the priesthood in general, and there was a generation gap between the faculty that remained and their students, according to Father Robichaud.

General Council of the Paulist community voted unanimously to terminate the status of St. Paul’s College as a degree granting institution on Jan. 20, 1971.

By the fall of 1971 a new model of seminarian education and training was introduced when Father George Fitzgerald was named both the superior of the college and formation director. The implementation of a “formation team” was in response The Program of Priestly Formation issued by the U..S Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1971 recommendations from an independent task force that a priority be given to a re-definition of what a formation program means and implement a pastoral program.

In this new paradigm, Paulist seminarians would receive their academic education at either Catholic University or the Washington Theological Union, which closed in the spring of 2012.

St. Paul’s College today

St. Paul’s College is in line with the contemporary standards of priestly formation, focusing on the four areas of human, spiritual, intellectual and pastoral development, according to Father Paul Huesing, CSP, rector of St. Paul’s College and the Paulist director of formation.

“In addition we add two additional components – liturgical and communal – for Paulist formation,” Father Huesing said.

Paulist students spend an average of six years in formation for the priesthood. During the first year, students (called novices at that point) are evaluated on “owning those six areas of formation and understanding the importance of them,” said Father he cumulative ministry of hundreds of Paulist Fathers that is the legacy of St. Paul’s College, according to Paulist President Father Michael B. McGarry.

“For most Paulists over the last 100 years, St. Paul’s College was the place where they learned what it means to be a priest, to be a Paulist, to be a brother,” he said. “There they absorbed Hecker’s vision of a mission to North America and there their roots were nourished. Finally, as an educational institution, St. Paul’s College gathered generations of Paulist faculty who taught philosophy, theology, history, creative writing, missiology, public speaking, and the myriad skills required for a Mission to Main Street. What a rich blessing for us, what a blessing for the American Church!”